Intestinal parasites are those organisms that live and complete a part of their life inside the host’s body. The parasites reside in the internal organs, GI tract, lumen, tissues, and body cavities. The parasites get nutrition from the host and cause damage to the host by sucking blood and nutrition. Horses are affected by several internal parasites, and Strongyles are the most important parasites.

Importance of Strongyles in Horses

Strongylosis is an important parasitic disease in horses of all age groups. The term strongylosis is used to describe the disease caused by infection with the large strongyles, Strongylus spp and Triodontophorus spp, and small strongyles like Trichonemal cyathostomum. Equine Strongyles is usually due to a mixed infection of these parasites. A heavy infection characterized by loss of condition and anemia are common in horses of all age groups but especially in animals ages between 1 and 3 years of age.

Life Cycle of Equine Strongyles

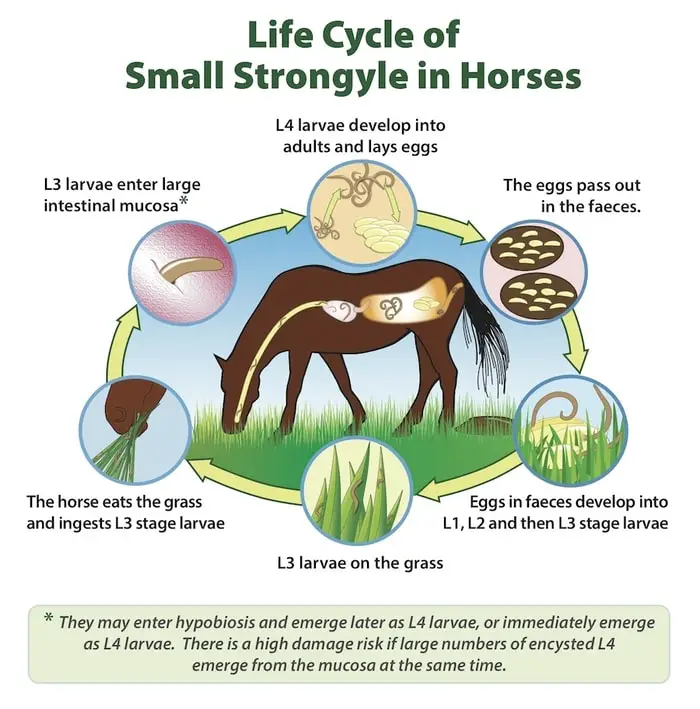

The life cycle of Strongylosis in horses are as follows:

- The adult parasites found in the cecum and colon are white or reddish-black and vary in length from 1 to 5 centimeters.

- Thin-shelled oval eggs of strongyle are passed in the feces, which develop to infective third-stage larvae on pasture.

- Infection is by ingestion of the L3, and only Strongylus spp subsequently embark on a migratory cycle within the host. The prepatent periods range from 6 to 12 weeks for the small strongyles and from 6 to 12 months for large strongyles.

Epidemiology Equine Strongyles

Strongylosis is a problem mainly in young horses reared on permanent horse paddocks. The source of these infections is two-fold: larvae which have overwintered and, more important, which develop in the current grazing season from eggs passed in the feces of untreated horse sharing the same grazing. Thus, infection builds upon the pasture through the summer months. Evidence suggests a similarity between Type II bovine Ostertagia and diarrhoeic syndrome of larval Cathostomiasis seen in horses in late winter or spring.

Pathogenesis Strongylosis in Horses

The pathogenesis of these worms is based on damage to the mucosa, whether from the feeding of the adult worms or the disruption caused by the emergence of the larval stage of the small strongyles.

- Adult large strongyles remove plugs of mucosa or submucosa, including blood vessels, whereas adult Trichonemas, due to the smaller size of their buccal capsules, feed more superficially, causing relatively minor mucosal damage.

- The worms appear to feed entirely on the cellular matter, but the damage to small vessels in the mucosal plug means incidental blood loss.

- Ulcers result from the bites of large strongyles, but except for some Triodontophorus, which feed in groups and may cause persistent large ulcers, these usually heal rapidly.

- Another cause of damage is the return of the migratory Strongylus spp as young adults.

- These worms are enclosed in large purulent nodules in the gut wall, which eventually rupture into the lumen so that there is local damage involving all the layers of the gut.

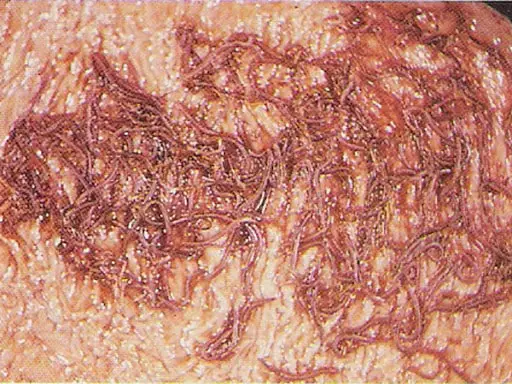

- Thousands of tiny strongyle larvae may be present in small nodules in the large intestinal mucosa. These may cause catarrhal or hemorrhagic enteritis with thickening and edema of the mucosa in animals six months to 6 years of age.

- Also, the acute syndrome of larval Cyathostomiasis with severe enteritis leads to diarrhea. In some cases, death may occur in heavily infected animals in late winter or spring associated with the mass emergence of large numbers of tiny strongyle larvae from the intestinal wall.

- In Strongylus vulgaris, the larvae migrate after ingestion from the gut via the intestinal arteries to the cranial mesenteric artery.

- The mature larvae return via the arterial tree to the large intestine.

- A large percentage of horses show lesions in the arterial system, generally involving the cranial mesenteric artery, the lesion being one of thrombus formation with marked thickening of the arterial walls.

Clinical Findings of Strongyles in Horses

Strongylosis is mainly seen in animals up to 2-3 years of age with severe infection, and the main clinical signs are unthriftiness, anemia, and sometimes diarrhea.

In older animals, severe infection may also occur, but marked clinical signs are less common, although general performance may be impaired.

The syndrome of larval Cyathostomiasis is one of sudden onset diarrhea, which becomes chronic and is associated with marked rapidly progressive weight loss leading to emaciation and, in some cases, death.

Cases are usually seen in young animals during late winter and early spring, and some may show signs of colic and subcutaneous edema.

In many cases, a large number of bright red larvae are shed in the feces.

Clinical syndromes in foals experimentally infected with S vulgaris are pyrexia, anorexia, and colic, which occur within a few weeks of infection. Still, such clinical syndromes are rarely reported from the field.

Clinical Pathology of Equine Strongylosis

In individual cases of Equine Strongylosis, strongyle egg counts in feces are difficult to prognosis since the level of egg output gives less indication of the number, species, and stages of development of the worms present.

Also, larval cultures are necessary to differentiate between Strongyle eggs and Trichostrongylus axei, a relatively common stomach parasite of horses.

Eggs count from a group of animals sharing the same pasture area of value both as a direct measure of potential pasture contamination with infective larvae and monitoring the success of any anthelmintic control program.

Although not specific, most cases of Strongyles and larval Cyathostomiasiswill show evidence of anemia, eosinophilia on hematological examination, and serum albumin level will provide below.

A hyperglobulinaemia involving beta globulins has been associated with larval infection of both the small strongyles and S vulgaris.

Post-mortem Findings of Strongyles in Horses

At Postmortem, there is evidence of anemia and poor body condition associated with a large number of different species of strongyles on the surface of the cecum and colon and the large intestinal mucosa.

Lesions will be included hemorrhagic spots or equine ulcers caused by the ingestion of adult parasites, with inflammation and accumulation of fluid of the mucosa and enlargement of associated lymph nodes.

Many coiled, developing, small, strongyle larvae may be seen on close identification of the mucosa, and there may be several necrotic nodules resulting from recent larval emergence.

These nodules can involve extensive areas of the large intestinal mucosa in cases of larval Cyathostomiasis.

S vulgaris larvae may be found in combination with thrombosis, thickening of the cranial mesenteric artery, and inflammation.

Infarction and necrosis of parts of the GI tract have been seen within a few weeks after experimental infection with S vulgaris due to arteritis and thrombosis of small arteries close to the intestinal wall.

Patches of sub-serosal bleeding may be seen due to the migration of S edentates larvae in the flanks.

Diagnosis of Strongyles in Horses

- Strongylosis should always be found in young horses which have lost condition, mainly if they are anemic.

- The detection of strongyle eggs in the feces is of limited value in diagnosis as substantial worm burdens may be associated with fecal egg counts of only a few hundred eggs per gram due to their low egg output by adult worms.

- For example, in larval Cyathostomiasis, fecal egg counts may be negative, but many bright red larvae may be passed in diarrheal feces.

- In this case, there will also be a history of rapid, marked weight loss, and neutrophilia and hypoalbuminemia will generally be found on examination of the blood sample.

Treatment and Management of Stronylosis in Horses

The currently available broad-spectrum anthelmintics effective against adult and larval strongyles in the gut lumen are the Benzamidazoles, pyrantel, and ivermectin.

- However, of these, only two benzimidazoles, i.e., Oxfendazole and fenbendazole, and ivermectin, have been shown to have significant effectiveness against tiny strongyle larvae in the large intestinal mucosa.

- In the horses, anthelmintics are usually marketed for oral administration either in the feed, such as a powder or granules or for direct administration as a paste or suspension.

- There are a few reports of successful medication of cases of intermittent colic attributed to S vulgaris larvae with high doses of Thiabendazole on two occasions with an interval of 24 hours between treatment.

- The therapeutic effect of some modern anthelmintics, such as ivermectin, which has been shown to have activity against migrating S vulgaris larvae, remains to be evaluated in such field cases.

Control of Strongylosis in Horse

Although control programs on different horse establishments will vary according to conditions such as management and availability of grazing, the following measures will dramatically reduce the level of infection:

- Treat all animals with broad-spectrum anthelmintics every 4-8 weeks. The dosing interval is based on the period following treatment during which egg output will be suppressed and related to the drug’s activity against developing larval stages.

- Treat new arrivals and isolate for 72 hours before allowing them to join the resident group.

- Change to a chemically unrelated compound in successive grazing seasons to try to avoid problems of drug resistance.

- Good stable hygiene.

- Paddock rotation.

- They are reserving the last contaminated pastures for nursing mares and their foals.

- At the later stage of the grazing season, if the animals are peaceful, treatment with a compound active against tiny strongyle larvae in the intestinal mucosa should prevent larval Cyathostomiasis during late winter or the following spring.