Equine Infectious Anemia (EIA) occurs in horse population worldwide is characterized by antigenic variability of the causal viruses and by persistent infection. Affected animal remains viraemic and often suffer irregularly recurring episodes of horse disease. They become lifelong carriers of the virus. EIA is sometimes known to as “Swamp Fever” as most outbreaks occur in warm wet areas where hematophagous insects which transmit the virus are abundant.

Etiology of EIA

The EIA virus belongs to the retroviridae family which includes The human T-Lymphocytic virus (HTLV) and the Human Immunodeficiency virus(HIV) or AIDS virus. It is a Lentivirus and like other members of this sub-family such as Maedi Visna virus and Caprine Arthritis virus. It is associated with persistent, debilitating infections.

Epidemiology of Equine Infectious Anemia

EIA was first described in France in 1843 and has subsequently been reported in horses, mules, and donkeys, in Asia, Africa, North and South America, Australia, and occasionally in many Europian countries including the UK, France, and Italy. Several outbreaks have been recorded in serum production horses.

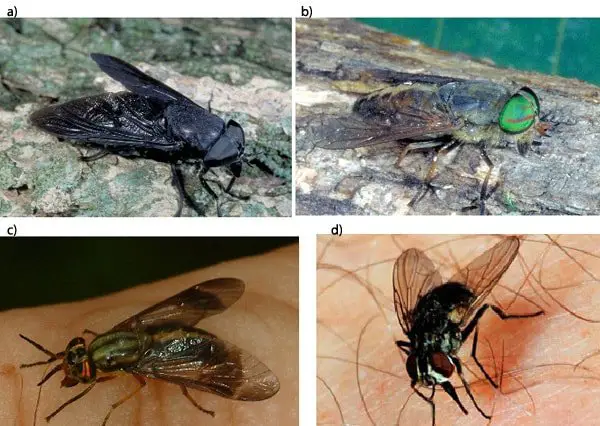

The virus is mechanically transmitted by biting flies or by contaminated needles, teeth rasps, stomach tubes and any other instruments which may cause abrasion. Horse flies, deer flies, stable flies, and mosquitos transmit the virus because of their large mouthparts; horse flies are the most effective vectors of EIA.

The virus is mechanically transmitted by biting flies or by contaminated needles, teeth rasps, stomach tubes and any other instruments which may cause abrasion. Horse flies, deer flies, stable flies, and mosquitos transmit the virus because of their large mouthparts; horse flies are the most effective vectors of EIA.

The disease mostly occurs during the summer and autumn, in marshy areas and river valleys. The virus may transmit transplacentally if the mare is a carrier. The foal may be affected after birth through colostrum of its mother.

The disease mostly occurs during the summer and autumn, in marshy areas and river valleys. The virus may transmit transplacentally if the mare is a carrier. The foal may be affected after birth through colostrum of its mother.

Clinical Signs of EIA

The disease may take an acute, chronic or sub-clinical course. The incubation varies from a few days to more than three months. The critical clinical signs are

- Fever.

- Edema of the depended parts.

- Hemorrhagic diarrhea.

- Jaundice.

- Petechial hemorrhage on the mucous membranes.

- Anemia.

- Death

The clinical Symptoms of the Chronic Forms are as follows:

The clinical Symptoms of the Chronic Forms are as follows:

- Progressive anemia.

- Loss of condition.

- Weakness.

- Tachycardia after exercise

Pathogenesis of Equine Infectious Anemia

The periodic nature of EIA appears to be due to antigenic changes of the surface glycoprotein of the virus and the regular release of new strains which evade the host immune system. In general, there is no cross-neutralization between different variants. When a new option is released, there is some delay before the horse adopts and produces antibodies which neutralize the virus.

Postmortem Lesions of EIA

The gross lesion is commonly seen include:

- Enlargement of the liver with accentuated lobular structure.

- Enlargement of the spleen.

- Lymphadenopathy.

- Anemia.

- Jaundice.

- Emaciation.

- Edema.

- Serosal Hemorrhages

Diagnosis of Equine Infectious Anemia

Hematological tests such as Platelet counts, a differential white blood cell count, the determination of Packed cell Volume and a Sedaroleukocyte count may be helpful indicators in EIA diagnosis but are not pathognomonic. Other diagnostic measures are ELISA, Coggins Test in many countries to diagnose EIA.

Hematological tests such as Platelet counts, a differential white blood cell count, the determination of Packed cell Volume and a Sedaroleukocyte count may be helpful indicators in EIA diagnosis but are not pathognomonic. Other diagnostic measures are ELISA, Coggins Test in many countries to diagnose EIA.

Treatment, Management, and Control of EIA

The antigenic variation of the virus present a significant obstacle to the development of an efficacious vaccine. No vaccine of proven efficacy is currently available.

Blood transfusion and fluid therapy may assist in recovery from clinical disease, but there is no effective means of eliminating EIA virus from an infected horse.

The prevention of EIA is based primarily on the detection of infected horses by the Coggins test and their isolation from other horses.

Since infected horses are the only known reservoir of the virus, it is entirely feasible to eradicate from an area by testing and slaughter of reactors.

Control of vectors by drainage of swampy areas and by the strategic use of insecticides may help to reduce the further infection of the disease.