The serological survey indicates that the Equine Arteritis Virus(EAV) is widely distributed throughout the world. However, clinical diseases are a relatively rare occurrence. It is the abortion-causing potential of the virus, which causes international concern and often leads to restriction on the movement of seropositive horses. The 1984 outbreak in Thoroughbreds in Kentucky leads to a temporary restriction on the export of all equine breeds from the USA to the tripartite countries (UK, France, and Ireland). This was subsequently replaced by the restriction on the export on any horse either vaccinated against equine viral arteritis or seropositive following natural infection.

What causes Equine Viral Arteritis?

EAV is an enveloped spherical RNA virus. For many years it has been classified as belonging to the non-arthropod borne group of Toga viruses. However, the recent determination of the nucleotide sequence of the genome of EAV indicates that the virus is related to viruses from the coronaviruses like superfamily. Only one serotype has been identified, but some genetic heterogeneity among strains of EAV has been detected using the oligonucleotide fingerprint technique.

Epidemiology of EVA

A. Distribution. The first recognized outbreak of EVA occurred on a standardbred stud in Bycurus, Ohio, in 1953, but the description of the disease “Epizootic cellulitis-pinkeye” in the veterinary literature date back to the late nineteenth century. Despite the apparent world-wide distribution of EVA, disease outbreaks appear to be infrequent and sporadic in nature. Serological evidence of the presence of the virus has been reported in Australia, America, Africa, and Europe. Evidence of exposure to EAV has been noticed in Standardbreds, Thoroughbreds, Quarter Horses, Arabian horses, and Warmbloods. Considerable differences in the prevalence of seropositive horses occur between certain breeds within a country. In America, Australia, and Newzealand, EAV is endemic in Standardbred horses but rare in Thoroughbred horses.

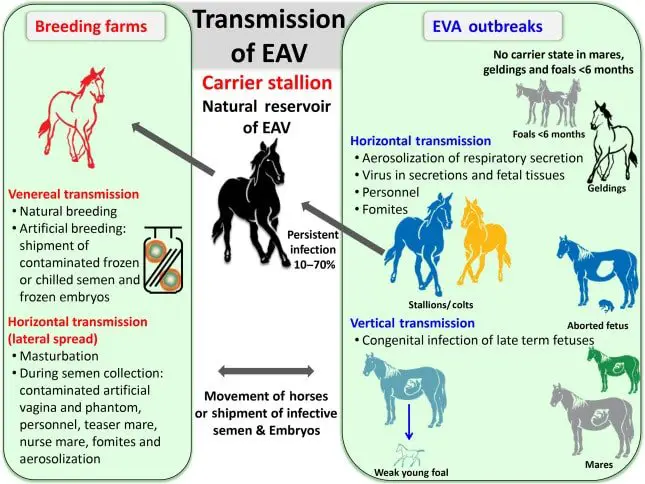

B. Transmission. The disease has not recorded in the clinical form in Japan or Ireland, but outbreaks have been recorded in several Europian countries, including Switzerland, France, Poland, and Spain, as well as in the USA and Canada. The EAV transmitted by the respiratory and venereal routes to other animals. The disease also spread by indirect contact with fomites. Aborted fetuses are heavily contaminated with viruses and are the source of infection. Carrier Stallion plays a vital role in the spread of the virus. A high proportion of EAV-infection stallion may become long-term carriers and shed virus constantly in the sperm rich portion of their seminal fluids. Such stallion does not appear to viraemic, nor do they shed virus in nasal secretions or urine.

Clinical Signs of Equine Viral Arteritis

Clinical manifestation of EAV infection is extremely variable, and the majority of infection appears to be sub-clinical. The most prevalent clinical signs are fever, depression, inappetence, limb edema, especially of the hind limbs, stiffness in gait, inflammation of conjunctivae, and nasal mucous membrane urticarial rashes, and edematous plaques, ocular and nasal discharge, palpable edema and edema of the orbital fossa. Moreover, edema of the mammary gland is frequently seen in mares, and the majority of stallions develop scrotal edema. Abortion may take place in mares in mid to late gestation.

Post Mortem Findings of EVA

The gross and microscopic signs associated with EVA are consistent with the predilection of the virus for the media of the artery. In the original Bucyrus outbreak, edema, congestion, and petechial hemorrhage of the lymph nodes, the subcutaneous tissues and many of the organs were noted. The predominant microscopic lesion was a widespread necrotizing artery. The pathological examination of the aborted fetus revealed edema of the lungs, increased pleural fluid, and petechial hemorrhages of the pleural and peritoneal surface. Cardiac myopathy and hemorrhages and edema of the brain have been observed in the fetus from other outbreaks.

Diagnosis of EVA

A. Clinical Signs. The diagnosis of Equine Viral Arteritis cannot be made solely on the clinical signs without corroborative virus isolation and serology. The serological diagnosis of EAV infection is based on seroconversion. If the first sample is collected during the acute stages of the disease, the convulsant sample should be taken 14-28 days later.

B. Serological Test. The virus can be isolated from nasal secretions, sperm cells, urine, buffy coats, and fetal tissues using a variety of cell lines, including rabbit kidney cells (RK 13). Recovery of viruses from experimentally infected horses rarely presents a problem, but it sometimes difficult to isolate viruses from naturally infected horses.

C. PCR. The PCR has been used to amplify EAV nucleotide sequences to facilitate their detection in seminal plasma. However, this technique is not yet used on a routine basis.

Management and Control of EVA

A. Treatment. Adequate rest with supportive therapy, if necessary, allows the majority of horses to make a speedy and uneventful recovery. Minimize the risk of the development of the chronic carriers; it is particularly important that affected stallions are allowed several weeks of sexual rest. It is also important to control pyrexia in the stallion as this may lead to a temporary loss of fertility.

B. Isolation of Affected Horses. The spread of EAV can be limited by the restriction of movement of horses from affected premice and where permissible, by vaccination with a modified live virus vaccine. Because of the lack of carrier status in the mare, a barren mare with stable or falling titers does not represent a significant risk to other horses. However, it is advisable to isolate an unvaccinated seropositive pregnant mare until she is foaled. Breeders who practice artificial insemination of non-Thoroughbred mares should only use germinal cells from the stallion that is seronegative for EAV or that have been shown conclusively not to shed viruses in their seminal fluids.

The Final Advice on Equine Viral Arteritis

The Equine Viral Arteritis in horses is a contagious infectious disease. This can be acute or chronic in nature, but the chronic form is very dangerous. In most cases, the virus remains dormant in the horses and transmit generation after generation. The infected stallion is very harmful for the horse breeder. Proper identification, treatment, and selection for breeding will help the horse breeder a lot.